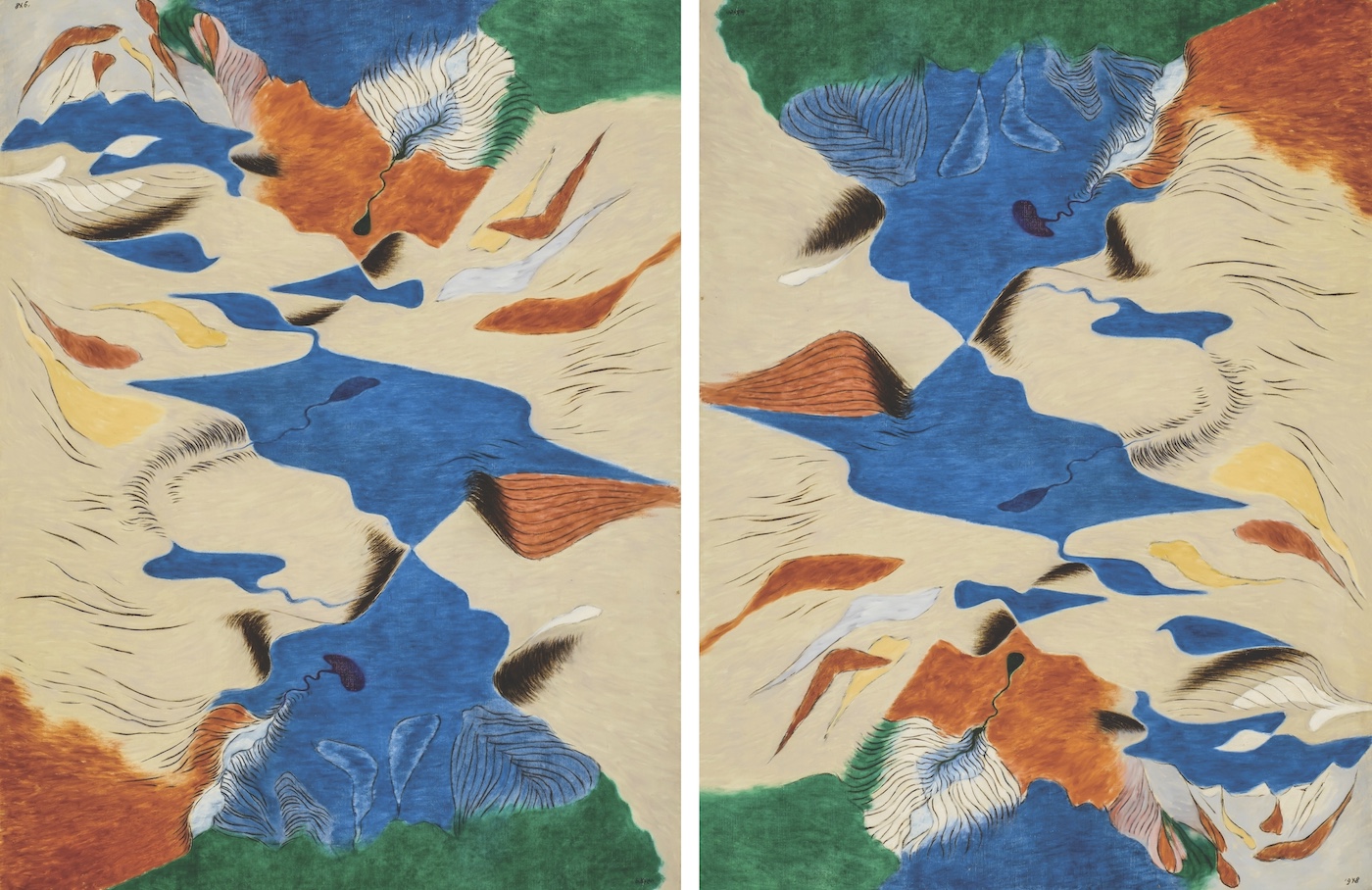

Mountains and Lakes, 1948/14, oil on canvas, 42 x 32 inches, Gift of the Family of Lillian and Gordon Hardy, 2025

Curator’s Choice: July 2025

Adam Thomas looks into the origins of Herbert Bayer's "two-way pictures"

In the late 1940s, Herbert Bayer created several works he called “two-way pictures.” The unusual designation refers to the dual orientation of these drawings and paintings—they can be rotated 180 degrees and presented, as Bayer noted, “inverted.” The 1948 painting Mountains and Lakes—recently given to the Aspen Institute and currently featured in the exhibition Sculpting the Environment: The Three-Dimensional Art of Herbert Bayer—belongs to this select group. Thanks to Bayer’s scrupulous recordkeeping, we know that Mountains and Lakes was the first painting to be labeled as such, though the previous year he had painted Wings over Mountain Valley (1947/3), the only instance of a “three-way picture” listed in his ledger. Two smaller black-and-white drawings now in the collection of the Denver Art Museum preceded Mountains and Lakes: Waterfall (1947/46) and Stratification (1948/11).

Like them, Mountains and Lakes shows natural terrain from above—without horizon line or sky the viewpoint is dizzying and free-floating. That the painting was designed to be turned and seen from different directions exacerbates this unsteady effect. The aerial landscape, that is, conjures a bird’s-eye or even cosmic perspective in which there is no inherently stable “up” or “down” orientation. The patches of blue, green, orange, and yellow undulate in a semi-abstract arrangement. Although Bayer was certainly not the first artist to experiment with reversible pictures, Mountains and Lakes calls attention to the connection between reversibility and the foundations of abstract art.

The idea of a picture whose orientation is uncertain or flexible is central to the lore around the development and difficulty of abstraction. For instance, British painter J. M. W. Turner’s increasing hazy and atmospheric works of the 1830s confounded many viewers, and a critic wrote of one interior: “We do not know what is represented; it seems as if the picture might just as well hang upside down.”(1) Similarly, Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky, an early artistic hero of Bayer’s and originator of pure abstraction, had an epiphany when, in the half-light of dusk, he glimpsed one of his own landscape paintings “leaning against the wall, standing on its side” in his studio: “I rushed toward this mysterious picture, of which I saw nothing but forms and colors, and whose content was incomprehensible.”(2)

Bayer’s “two-way pictures” suggest a playful awareness of this strand of art history. Without relinquishing representational subject matter altogether, they intentionally test the adequacy and power of form, line, and color through inversion. Perhaps even more significantly, for Bayer was an artist deeply concerned with how we see the world, they also evoke the nature of sight itself: we perceive the world right-side up, but the image projected onto the retina is inverted.

Adam Thomas, PhD is Curator of the Resnick Center for Herbert Bayer Studies.

(1) Josef Strzygowski, “Turner’s Path from Nature to Art,” Burlington Magazine 12 (1908): 341.

(2) Wassily Kandinsky, “Reminiscences” (1913), in Modern Artists on Art, ed. Robert L. Herbert (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2000), 29.

more