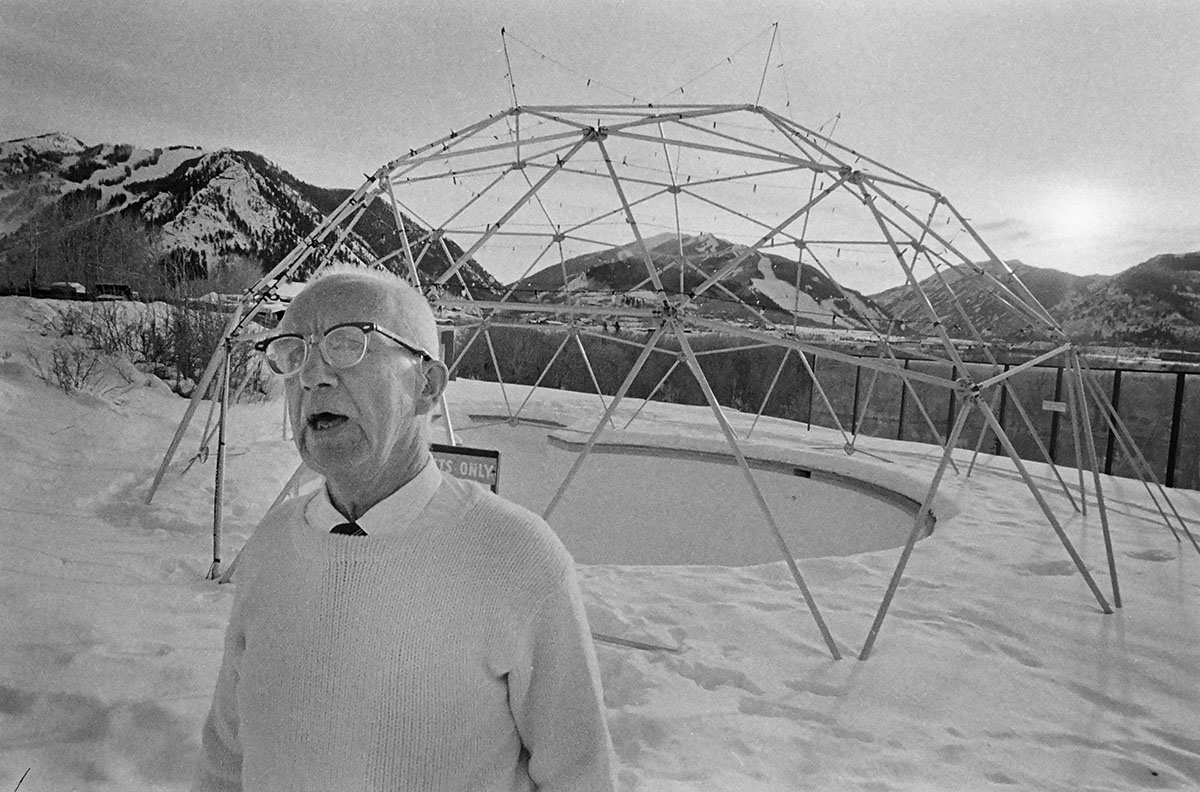

Buckminster Fuller with his geodesic dome on the Aspen Institute campus, January 1967. Credit: Aspen Historical Society, Hiser Collection

Buckminster Fuller’s Aspen

The Bayer Center's Andrew Travers recounts local and global impact of 'the planet's friendly genius' in partnership with Aspen Film

I gave a short talk in May on the designer, architect and futurist Buckminster Fuller as part of Aspen Film’s Science on Screen series at the Isis Theatre. As is often the case in Aspen, the audience upstaged the speaker—more than a half-dozen people in the audience of about 60 included Aspenites who had worked on Fuller’s local projects, heard him lecture in person and (in one case) were held by him as an infant.

Those personal connections spoke directly to my subject: Fuller’s intimate and inspiring involvement in Aspen from the early 1950s up to his death in 1983 at age 87, including work with the Aspen Institute in its early years and collaborations with John Denver’s Windstar initiatives later.

Across those three decades, this very short, very passionate New Englander known as “the planet’s friendly genius” became one of the most famous people in the world for his ideas and inventions.

To demonstrate part of his effect on our lives today, I started my talk by asking how many people in the audience knew the word “synergy.” Of course, every hand in the audience went up as the word is seemingly inescapable today in the lexicon of business marketers and youth basketball coaches and the rest of us. Not so in Fuller’s time. Fuller would often open his lecturers asking about the word, which few if any would recognize, as an entree to his concepts. It’s ubiquitous today because he spread the idea of synergy and parts creating a greater whole.

Fuller is remembered for concepts like “Spaceship Earth” and “ephemerization” and “tensegrity,” but the two concepts I focused on were his Dymaxion Map and his geodesic dome, both of which he worked on for Aspen projects and both of which feature prominently in the film “The House of Tomorrow,” which screened after my talk.

“Dymaxion,” one of many words Fuller coined, combines “dynamic,” “maximum,” and “tension.” He had created a Dymaxion House in the 1920s and a Dymaxion Car in the 1940s (one audience member said he was part of a team currently building a replica!). Fuller’s twenty-sided Dymaxion Map sought to create an accurate two-dimensional representation of Earth, free of the distortions that plague map projections. When flat, this icosahedron shows most of Earth’s land masses as a contiguous form, and can be folded to create a model of the planet. Patented in 1946, the Dymaxion Map was admired by Aspen’s Herbert Bayer, who used it in his World Geo-Graphic Atlas to demonstrate global energy consumption.

The Bayer Center’s ongoing exhibition “Charting Space: Herbert Bayer’s World Geo-Graphic Atlas at 70” includes this video animation of Fuller’s Dymaxion map as utilized by Bayer:

Bayer was working on his atlas in Aspen from 1947 to 1953, the period when Fuller first came to town.

From what I could find in my research, Fuller’s first trip here was for the International Design Conference in Aspen in 1952. The legendary gathering of designers, architects and artists — co-founded by Bayer — had launched the year before. Fuller would be a regular presence on the Institute campus for the conference as both he and it rose in stature in the three decades that followed.

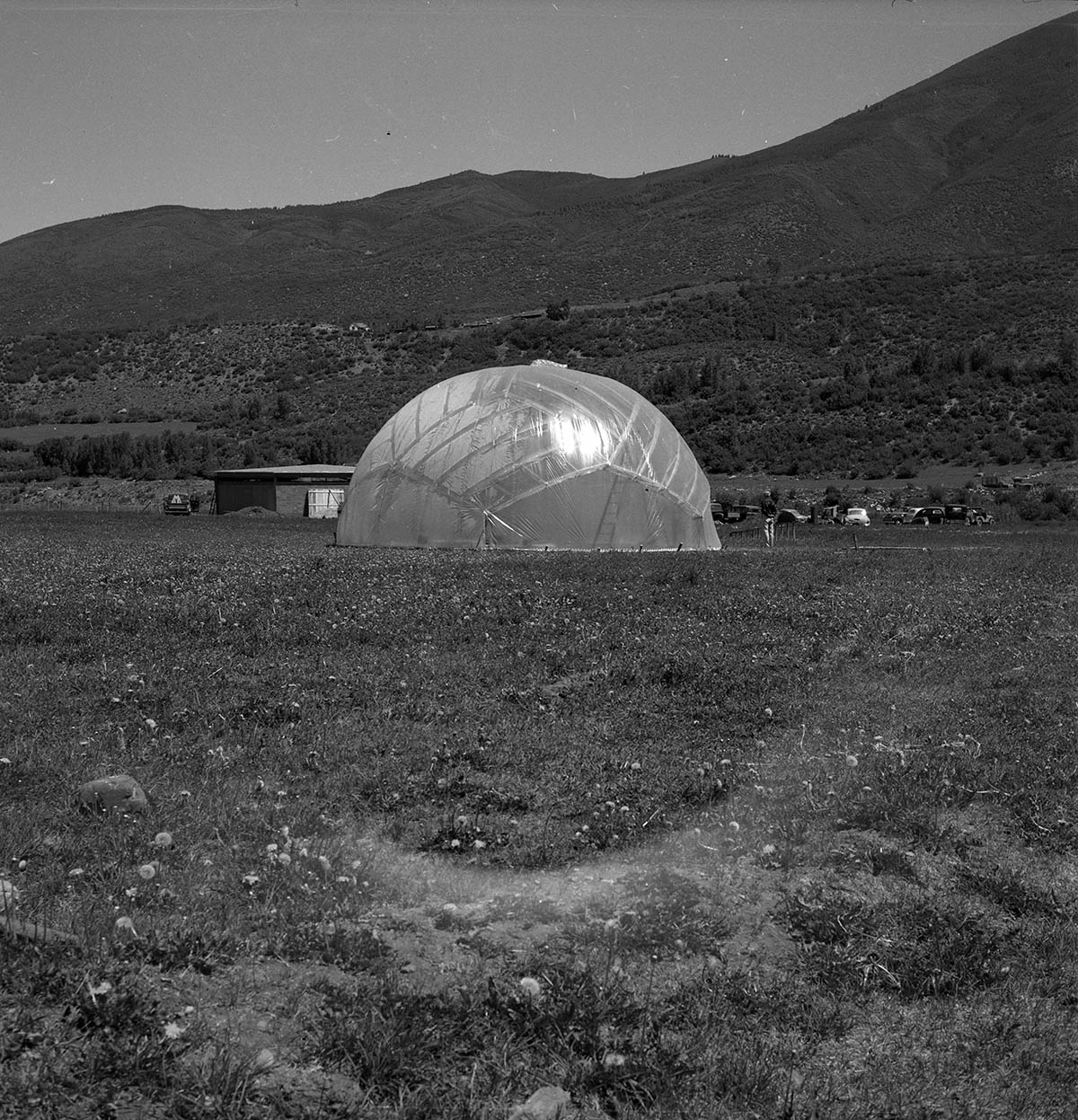

At the following year’s conference, Fuller returned and built one of his first geodesic domes on the Aspen Institute campus:

Fuller's temporary dome constructed for the 1953 International Design Conference in Aspen. Credit: Aspen Historical Society, Mary Esbaugh Hayes Collection.

The Aspen Times on July 30, 1953 reported that the dome “was erected during the Design Conference near the Big Tent by 20 University of Minnesota students. The bubble-shaped structure is mass-produced, inexpensive and quickly put up (in two hours). It is made of many wooden triangles and fibre glass cord, covered with transparent plastic material. It is very strong and will carry heavy snow loads. One of the interesting talks of the conference was one on geodesic domes given by Buckminster Fuller.”

It wasn’t the first geodesic dome — Fuller had tried others out in Massachusetts and at Bennington College before — but the 1953 Aspen dome was among his first and demonstrated his theory that it could house a large area with few cheap materials. He patented his iconic design a year later.

The structure would later become immensely popular and intrinsically linked to Fuller, including large and iconic domes like the Montreal Biosphere (1967) and Epcot Center at Disney World (1982).

Fuller constructed a more permanent geodesic dome for the Aspen Institute in 1955, which was placed above the Herbert Bayer-designed campus pool.

Fuller's dome over the Aspen Institute pool in 1955. Photo credit: Aspen Historical Society, Durrance Collection.

Photo credit: Aspen Historical Society, Ringle Collection.

As the Times reported it upon its opening to the public that summer:

“THE GEODESIC DOME, a dome structure built up of lightweight structural members and braced by wire, supports a plastic dome covering for the new swimming pool designed by Herbert Bayer at the AIHS Chalets. The entire unit is so light that 3 or 4 men can easily remove it if the shade is not needed. Buckminster Fuller, designer, has produced this experimental model to show what can be done with lightweight materials through his company, Geodesies, Inc.”

Fuller's dome and Bayer's pool photographed in the summer 1974. Photo credit: Aspen Historical Society.

The dome remained at the pool for decades, as Fuller continued returning to Aspen. Most often his extemporaneous lectures at the Institute through the 1950s, ‘60s, ‘70s and into the 1980s were titled “Man and His Universe” because he was known to jump across countless topics and ideas in them.

Author Patwant Singh, then of Design Magazine, under Fuller's dome with participants of the 1964 International Design Conference in Aspen. Photo credit: Aspen Historical Society, Durrance Collection.

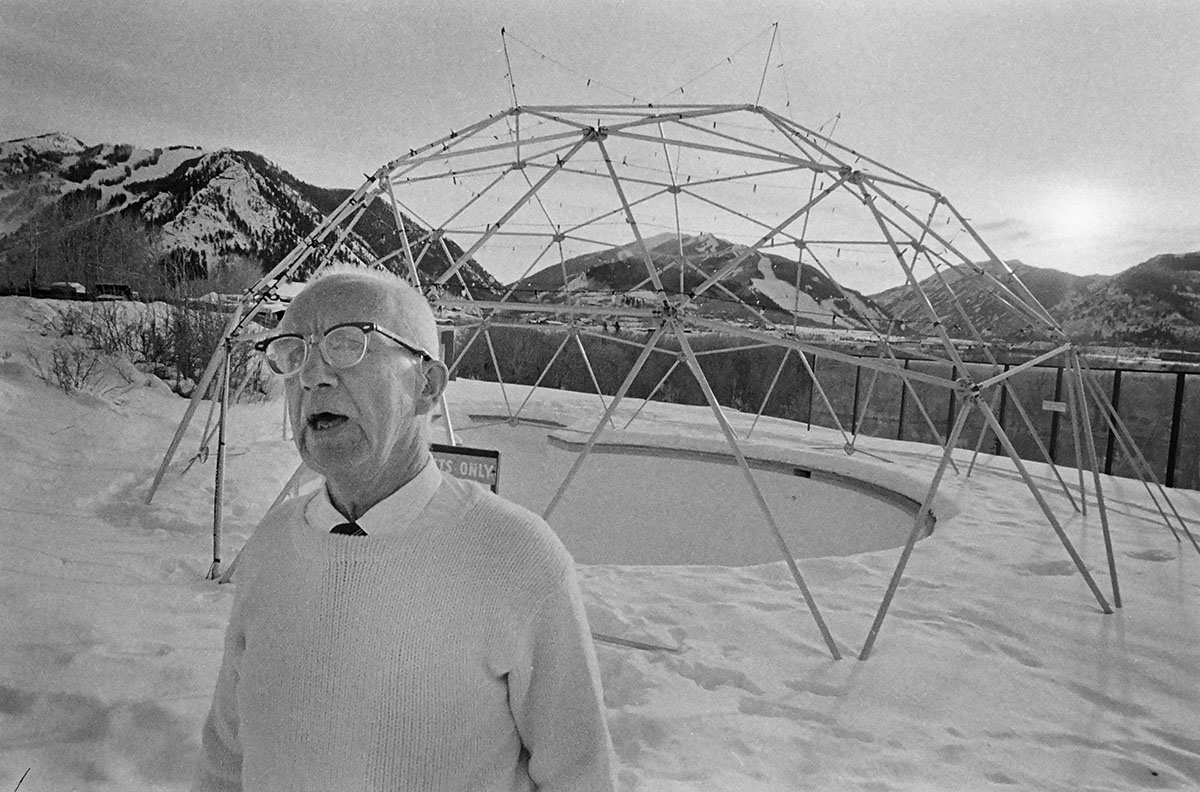

Fuller connected with organizations beyond the Aspen Institute as well, speaking at programs of the Aspen Music Festival and others. A visit to give a keynote for the Young Presidents’ Organization here in January 1967 marked a rare wintertime visit for Fuller.

Fuller with his geodesic dome on the Aspen Institute campus, January 1967. Photo credit: Aspen Historical Society, Hiser Collection.

Fuller reportedly tried skiing — with the Aspen ski school legend Fred Iselin, no less — on that visit, and expressed his admiration for skiers for “working with gravity, rather than against it.”

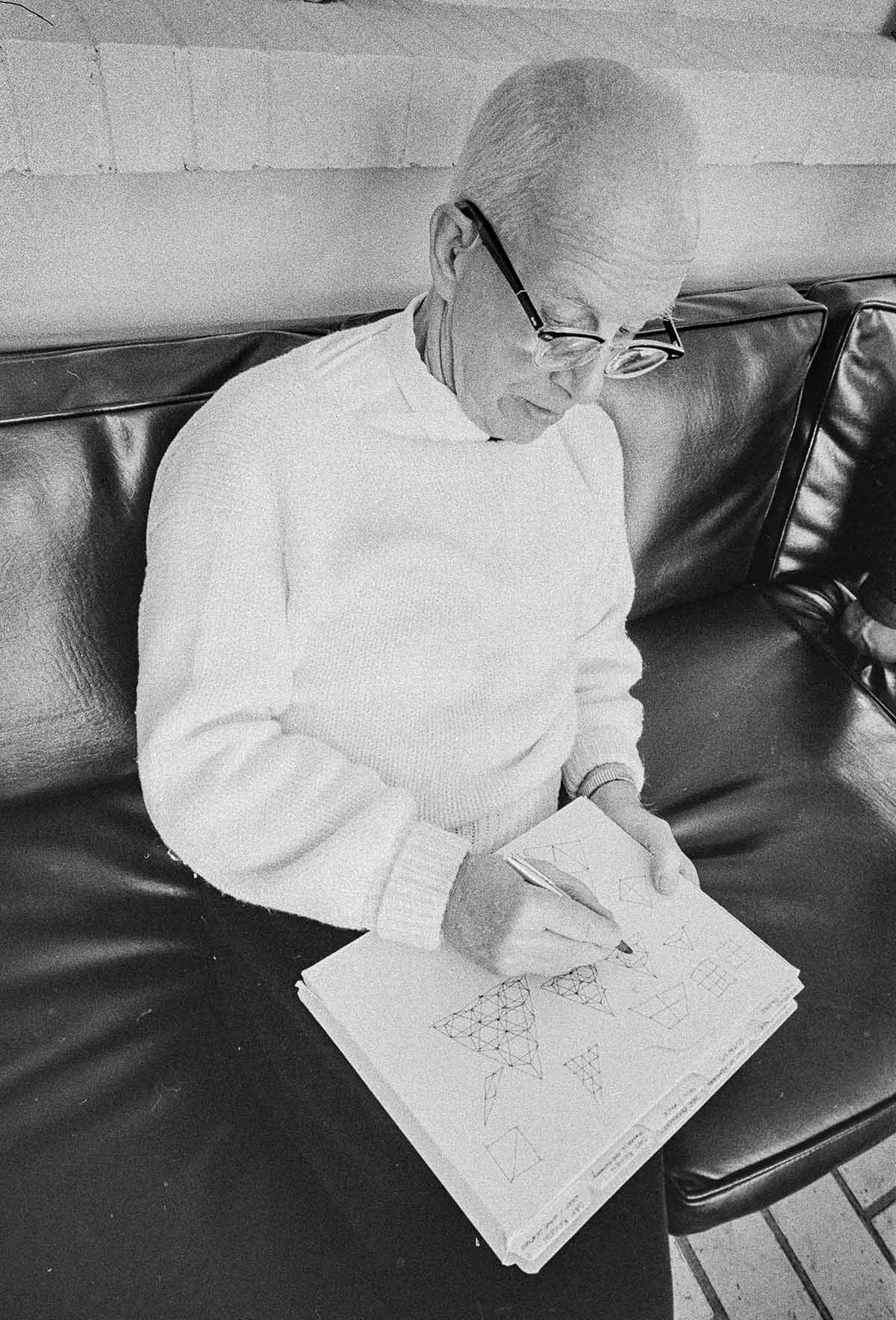

Fuller sketching in Aspen, 1967. Photo credit: Aspen Historical Society, Hiser Collection.

Est founder Werner Gerhard (left), Fuller (center), and John Denver (right) at Windstar in 1980. Photo credit: Aspen Historical Society, Aspen Times Collection.

Fuller connected with John Denver in Aspen as the folksinger rose to prominence and took on increasingly ambitious environmental initiatives through his Windstar Foundation in Old Snowmass. Fuller and Windstar activists built several geodesic domes at the conservancy and Fuller worked with Denver and Est founder Werner Gerhard on their global Hunger Project initiatives.

Denver’s CBS affiliate interviewed John Denver about the Biodome project and his collaboration with Fuller at Windstar.

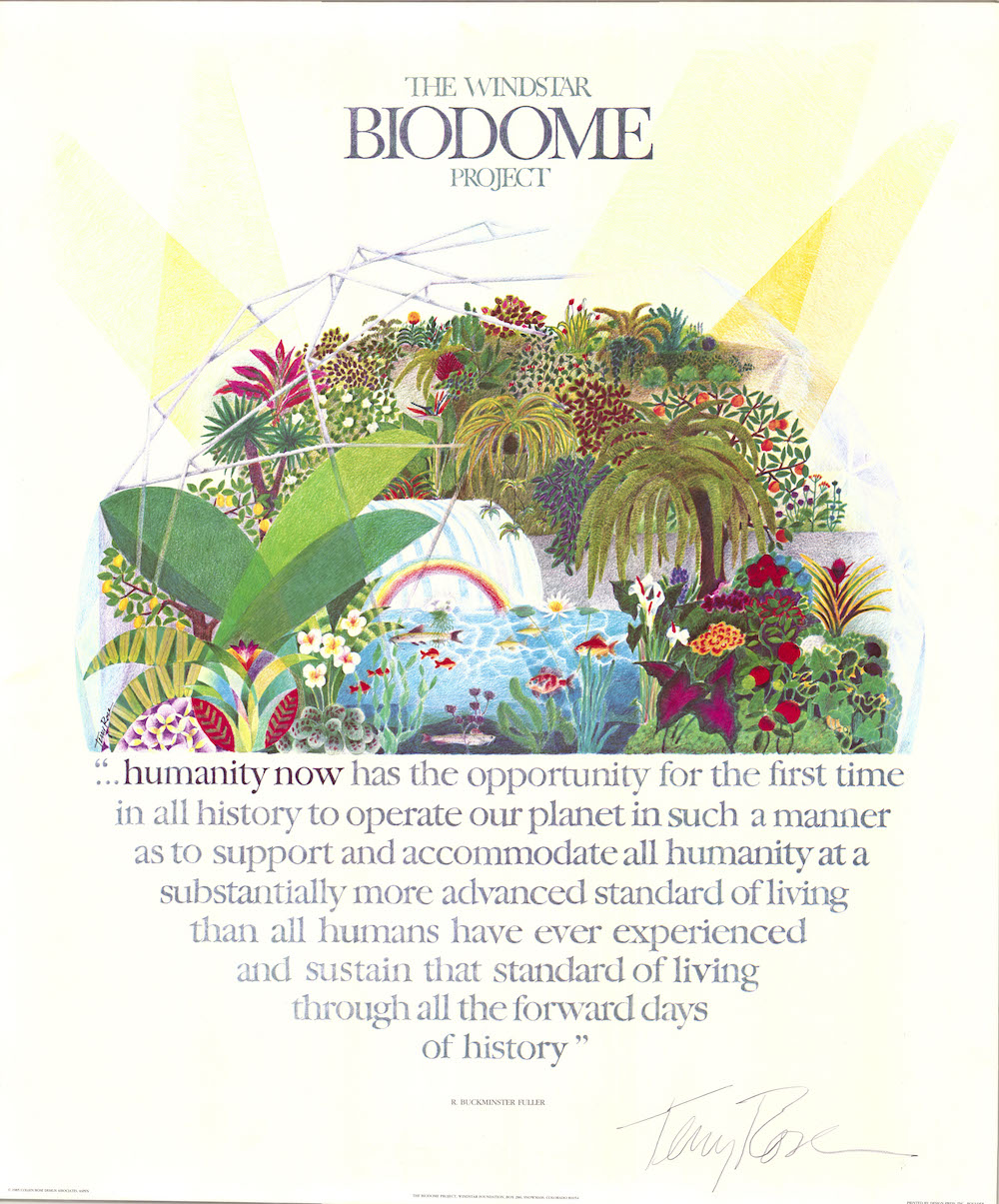

This 1985 poster from the Windstar Biodome Project features art work by Windstar art director Terry Rose and a quote by Buckminster Fuller.

Fuller had been working with Denver and Windstar in 1983 to complete the Windstar Biodome, which aimed to use solar power to raise crops year-round including the harsh Colorado winters. Fuller died of a heart attack just before a scheduled July visit to Windstar, but a crew of dedicated local architects and activists took up the job and completed the Windstar biodome, which proved successful and operated there until 1989.

Upon Fuller’s death, Windstar co-founder Tom Crum wrote: “Buckminster Fuller is known by most of the world for his great technological inventions and his clear insights into the working principles of the universe. But for us at Windstar, he was a grandfather of the fondest kind — the one who loved unconditionally and whose twinkle of the eye and compassionate heart made us feel five years old, sitting wide-eyed on Granddaddy’s lap, waiting for the next story. Whenever Bucky saw a child, he was drawn like a magnet to play and discover with him. Using his doctor-like little black bag, stuffed full of colorful tubes and hubs and connectors, Bucky could transform himself into a geometrical magic act, mesmerizing all ages in childlike wonderment. Permeating his expansive and brilliant mind was always an in-fant-like joy of seeing things new and fresh each day. His eyes were perpetually moist with awe and gratitude at the workings of God in everything around him. He did not separate technology from nature, and recognized the Divine in all of creation. Bucky at once blended his absolute trust in the Universe with the guts to stick his neck out for the common good. The need for public approval he discarded a long time ago, courageously pursuing his heart’s path. It is with great love and respect that we mark the passing of Buckminster Fuller. He was more than an advisor to us at Windstar: he was a total inspiration, and remains an irreproachable example of integrity for us all to follow.”

Fuller’s geodesic dome on the Aspen Institute campus was moved during renovations that relocated the pool area and filled in Bayer’s original. Today, the Buckminster Fuller dome is used for storage in the winter and hosts Institute events in the summer. It remains accessible near the center of the campus on the edge of Anderson Park.

Looking south over Buckminster Fuller's Geodesic Dome on the Aspen Meadows campus. Photo credit: Aspen Meadows.

Andrew Travers is the inaugural Penner Manager of Educational Programs at the Bayer Center.

more