Docomomo US Highlights Marble Garden Restoration with National Award

Jury Gives "Citation for Art Preservation” to Herbert Bayer Sculpture.

Aspen-based Design Workshop, Inc. and the Aspen Institute are proud to announce that the iconic sculpture, Marble Garden, designed by Herbert Bayer on the campus of the Aspen Institute has received an award for its restoration from the Modernism in America Awards Jury and Docomomo US. In bestowing the award, the jury noted that the unique nature of this land-art project warranted a special category. As such, it will be given a “Citation for Art Preservation” at an awards ceremony in Los Angeles, to be held in November at the Design Within Reach Showroom in West Hollywood.

Genesis of a Landscape Art Movement

The modernist landscape art of Herbert Bayer is the nucleus of the Aspen Institute’s 40-acre campus, inspiring visitors, participants, and the community with its artistic, intellectual, and enlightened ideals. Bayer’s design for the campus and its amenities is considered a true manifestation of the Bauhaus philosophy, uniting all artistic disciplines to create a total work of art. Conceived in 1949, during a post-war era in which participants of the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies contemplated a future that engaged broad categories of art, industry, and emerging social ideas, and where mind, body, and spirit met the intellectual, physical, and cultural challenges of the day.

Bayer’s masterpiece, produced from discarded marble pieces, is a boldly geometric and planar organization of layers of grass, marble, and water. The sculpture is widely noted for its landmark qualities, but like many extraordinary works of landscape architecture, immediate restoration was necessary to preserve the work, remediate safety concerns, and ensure its longevity. The narrow and heavy stone blocks, some which weigh more than 5000 pounds, were tilting precariously on a foundation that was sinking into the ground.

The Marble Garden’s meadow setting was unique for its time. Additionally, the sculpture’s origins and the designer’s intent are clear from archival research, review of Bayer’s drawings, writings and interviews. However, because there were no documented construction methods, it was not clear how the sculpture was constructed. In order to properly undertake reconstruction of the Marble Garden, a new design had to be created from eyewitness accounts, testing, sampling, and observation. Construction details required a forensic design approach to determine how best to achieve restoration. With the help of art curators and historic archives, a thorough research effort incorporated detailed measurements and surveys of each marble piece, including changes that occurred over time.

The design team conducted extensive research into the original placement and reorganization of the marble features over time. Interviews and art historical research revealed a deeper understanding of the artist’s original intent for the piece.

Research and Discovery

Project oversight was provided by the landscape architects who also relied on contributions from stone preservation experts, art curators, engineers, and contractors assembled to undertake the re-building process. Because Bayer produced an astonishing body of work that included architecture, graphic design, painting, exhibition design, and sculptural art, the art curators were able to investigate an array of written, photographic, audio, and video materials related to the Marble Garden, including the contextual and personality influences of the time period. And, while some sources suggest the original construction of the Marble Garden was haphazard, research proved that to be incorrect. Conceived in 1949, six years before construction, it is precise and purposeful, its large, marble pieces set on footings in a precise layout. Deterioration was determined to be due to poor surface drainage, inadequate foundations, overly thin concrete slabs, and bio-staining from organic materials. As a result of these conditions, the largest pieces in the composition were on the verge of collapsing.

Incidental photos over time show both additive and subtracted pieces on the base and many different compositional iterations. Some stones have been relocated, turned, and moved from horizontal to vertical positions, and the water jet has evolved. Archive sources suggest that the composition, including the arrangement of the marble and its location, satisfied Bayer. However, after that point in time, the blocks continued to migrate on their base, some moved by natural cause, others moved by human intervention.

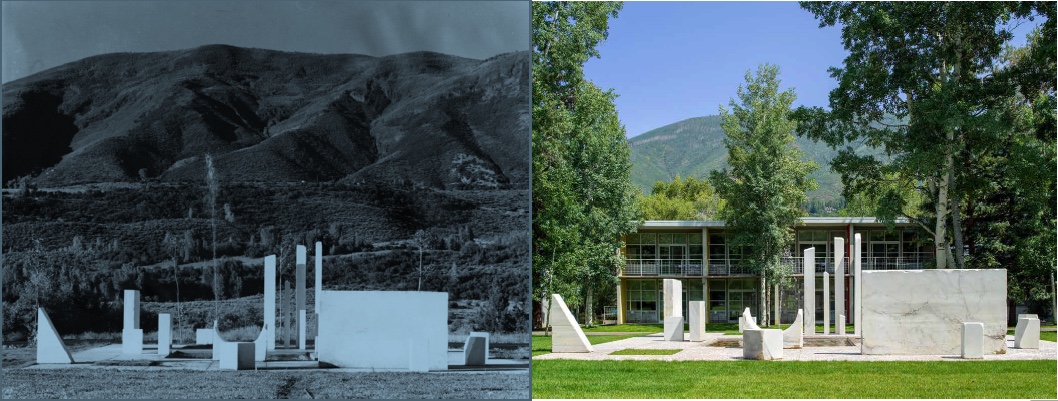

Left: The Marble Garden was re-constructed with authenticity and authority for the original art. Landscape art restoration required invisible design to intervene and support the innovation of the original vision. The visual relationships of the original campus plan and art was preserved.

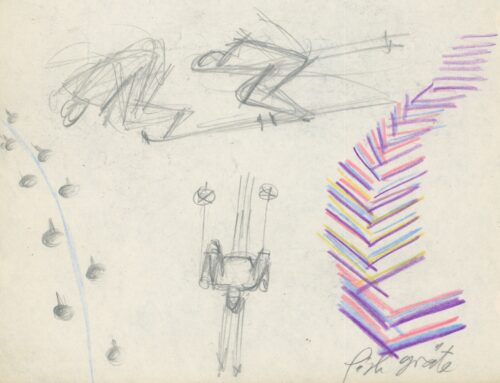

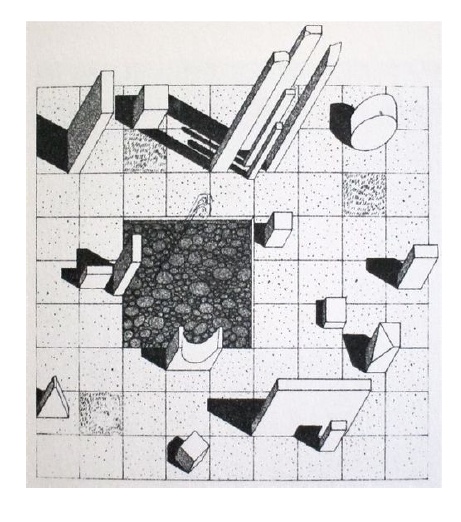

Right: Herbert Bayer made several conceptual sketches of the sculpture before it was built. Working within a 36’ x 36’ grid, he continued to move the marble pieces and water feature until he arrived at the final composition.

Invisible Design Reestablishes the Bauhaus Influence

The most damaged section of the sculpture was the base plinth into which approximately one quarter of the total marble pieces are embedded. Because the remaining marble pieces rested on top of the plinth, the design team had to ensure that the slab was appropriately graded to promote proper drainage while not impacting the tilting blocks. The result was an unconventional design with minimum pitches directing water over short distances to keep the stones vertical. A precise survey of the original ground plane grid resulted in the restoration of 4’x4’ squares that link together the entire layout. Original stone columns were braced with a complex framework of protective supports while work to the base and foundation occurred. The new foundation included slots that provided a means to remove the hoisting straps needed to move the stones. Hand work around the delicate shafts of marble ensured the prevention of any marring or breakage of the marble pieces.

A jet of water emerges from a water basin at the base of the sculpture. Documents describe this feature as everything from a bubbler to a jet of water 12 feet high. While aesthetics were a strong consideration, restoration focused primarily on the mechanical features of the jet. Ultimately, the team agreed that it was better to retain the original ½ hp submersible pump in the basin than attempt to replace it with a far more sophisticated mechanical system, particularly because preserving Bayer’s authentic artistic idea also included preserving any resources he used in its creation. The only additions to the original scheme include controls to manage windblown spray. A native red sandstone from the Frying Pan River cobble—a natural contrast to the white marble—that was used to line the basin was removed, cleaned, and returned to line the basin.

In order to understand how the Marble Garden was constructed, the team tested existing materials, sampled the underpinnings of the concrete slab, and sought input from the operations team that maintains Anderson Park. The structural integrity of the concrete and marble base was bolstered with a seeding of 3/8” – 1/2” inches marble chips, sourced from the Yule marble quarry where the original marble was found. Because marble crushing operations only produce large-diameter finished stone pieces, team members had to hand sort through piles of chips to find and match the needed sizes. Saw cut joints of the same dimension finish the ground plane. Drainage and moisture damage issues were resolved with grading and remediation of the soil base conditions.

Application of methods and means in landscape art

Of significant value to the landscape art movement are the subtle and hidden methods used to preserve the landscape setting and the sculpture set within it. While the intrinsic value of the Bauhaus is widely recognized across the nation and the world, its influence in Colorado is less known. Therefore, projects like this are important for historic preservation purposes and, equally as importantly, to fully complete the picture of modernism and its local and global influence. Realizing the effect this project could have on the greater arts community, the team devoted considerable effort to fundraising to make the restoration possible. While grant requests netted no results, the Institute recognized the safety hazards of the original Marble Garden feature and elected to proceed with restoration, fulfilling its stewardship role in protecting and enhancing a significant landscape art treasure on its campus.

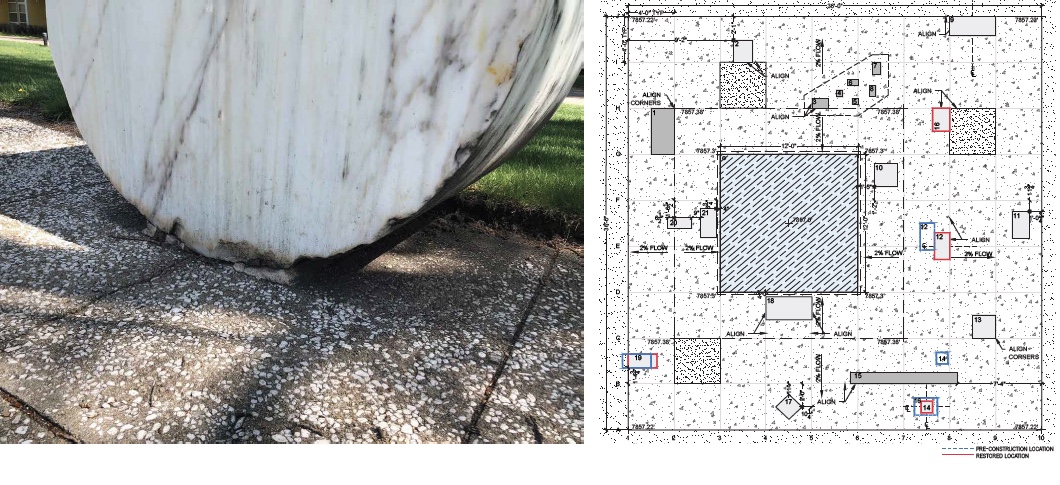

Upper Image: The marble pieces needed repair and stabilization. A detailed assessment of each stone occurred during cleaning of marble damaged by bio-staining and mold. Each piece was moved, stored, and replaced on the base in the correct orientation and position.

Lower Image: The stones, which weigh as much as 5,000 pounds each, were set on unstable foundations that had deteriorated due to poor drainage, inadequate footings, and inappropriately thin concrete slabs. The new foundation design provided for safe installation and stone setting.

Herbert Bayer was interested in the interaction of light and shadow on the sculpture. After restoration, his intention is fully realized on the 21 cleaned and reassembled marble pieces.

Design Value to a Community

At the time when Herbert Bayer began designing the piece, finding the marble, and assembling it in a vacant field, there was no sense that art and landscape could, or should, be integrated as one composition. Now, through an arduous process of revealing artistic intention and innovation, the importance of art in the landscape has been confirmed. The restored Marble Garden has been built to last in a landscape that celebrates art as the great unifier of people and place, and invites the public to experience and understand it through a living collection. As such, visitors are encouraged to, in the words of Bayer, “pause, sit and view the sculpture from a distance and interact with it closely”. The careful rebuilding of this work suggests an acknowledgment of the resources, knowledge, and craftsmanship required to complete the project. Utilizing landscape architecture as a method for discovery, through research and applied knowledge, was essential for restoring, protecting, and enhancing this unique piece of modernist landscape art for years to come.

Text Credit: Design Workshop

Photo Credits: Design Workshop, Sarah Shaw, Aspen Institute

more